I was giving a presentation on choice in the NHS last night (thank you, Darzi alumni fellows) between the crucial hours of 7 and 8 in the evening, so I have had to watch the Clegg-Farage clash this morning – or as much of it as I could.

My impression was very different to the polls which have handed the victory so spectacularly to Farage.

I thought that Clegg was effective, articulate, passionate and authentic. He took on Farage’s populism in a way that neither Cameron nor Miliband would have been able to do. It was a ferocious performance and an important moment, I thought, in our political history.

But the polls are not to be ignored, which means that the important moment may also be a worrying moment for the nation.

It is also tremendously important, for the forces of light, that we can be as honest as possible about why Farage was widely seen to have won, and I have three thoughts about this.

Thought #1. Clegg was emotional, but Farage was emotionally connected.

There was a controlled leak from the Clegg camp in the

Guardian before the second debate which suggested that Clegg was going to be “more emotional”. He was, and it was effective. The trouble was, that wasn’t precisely what was required.

What Farage managed to do was not to be emotional – a scary prospect – but to draw on the emotions of those watching in his arguments. He was able to appeal to gut emotions and gut values in the way that Drew Westen showed that George W. Bush managed to against Al Gore’s statistics in his book

The Political Brain.

It isn’t emotions in the politicians that we need; it is their ability to conjure emotional commitment in the voters. That is a very different matter and, as far as I can see, Clegg’s party has given very little thought to it.

Worse, all three of the big Westminster parties regard this sort of consideration with lofty disdain, bordering on fear, as if any involvement of the emotions in the electorate will conjure up the Gordon Riots all over again.

Thought #2. Farage has the time to think; Clegg doesn’t

The irony is that Clegg is precisely the kind of gut politician who is capable of doing this, but he suffers from a major disadvantage now. He is deputy prime minister. He is imprisoned in the system in 70 Whitehall where he is given no time to think for himself.

His every moment is concerned with detail and immediate response and he has surrounded himself with brilliant people who are extremely good at helping him with these immediate problems. But when it comes to drawing on new thinking, outside the prevailing and – let’s face it – rather tired and therefore vulnerable assumptions of the establishment, he has had to put it off for the last four years.

He is forced to draw on the old arguments, the assumptions that trade negotiations will result in widespread jobs and well-being, for example – which a dwindling number of us believe – because he exists in a Whitehall bubble that starves his creativity. Farage doesn’t. It puts him at a major advantage.

Thought #3. If Farage is allowed to be the only outsider, he will win.

Farage has shifted his position. He is now explicitly against “big business”, though it is hard to see anything substantive which he has ever said on the subject. But this is a significant widening of his message

If that means the banking scandal, the Libor scandal, the scandal of executive pay, and the way the manipulation of the world’s economic system in favour of a tiny elite has failed to trickle down – then so am I. So is nearly everyone.

Farage has realised how the barrage of statistics used by the establishment to defend EU membership, and the union with Scotland come to that, alienates as much as it enlightens. We know, after all, the limits of their applicability.

Let’s be personal about this. I have been a Liberal since 1979. I absolutely deny that this makes me some kind of insider or beneficiary.

I deny that Lib Dems in government, and Nick Clegg in particular, are Whitehall insiders. Quite the reverse, every step forward is an exhausting struggle against vested interests. I deny that the progress the party has made in government means we now have to defend the status quo.

As a Lib Dem, I don’t have to defend the lazy short-termism of the biggest businesses. I don’t have to pretend that backing enterprise means backing multi-million pound salaries for those who corrode the economy. I don’t have to defend the status quo, and – if I try to – I will lose the debate.

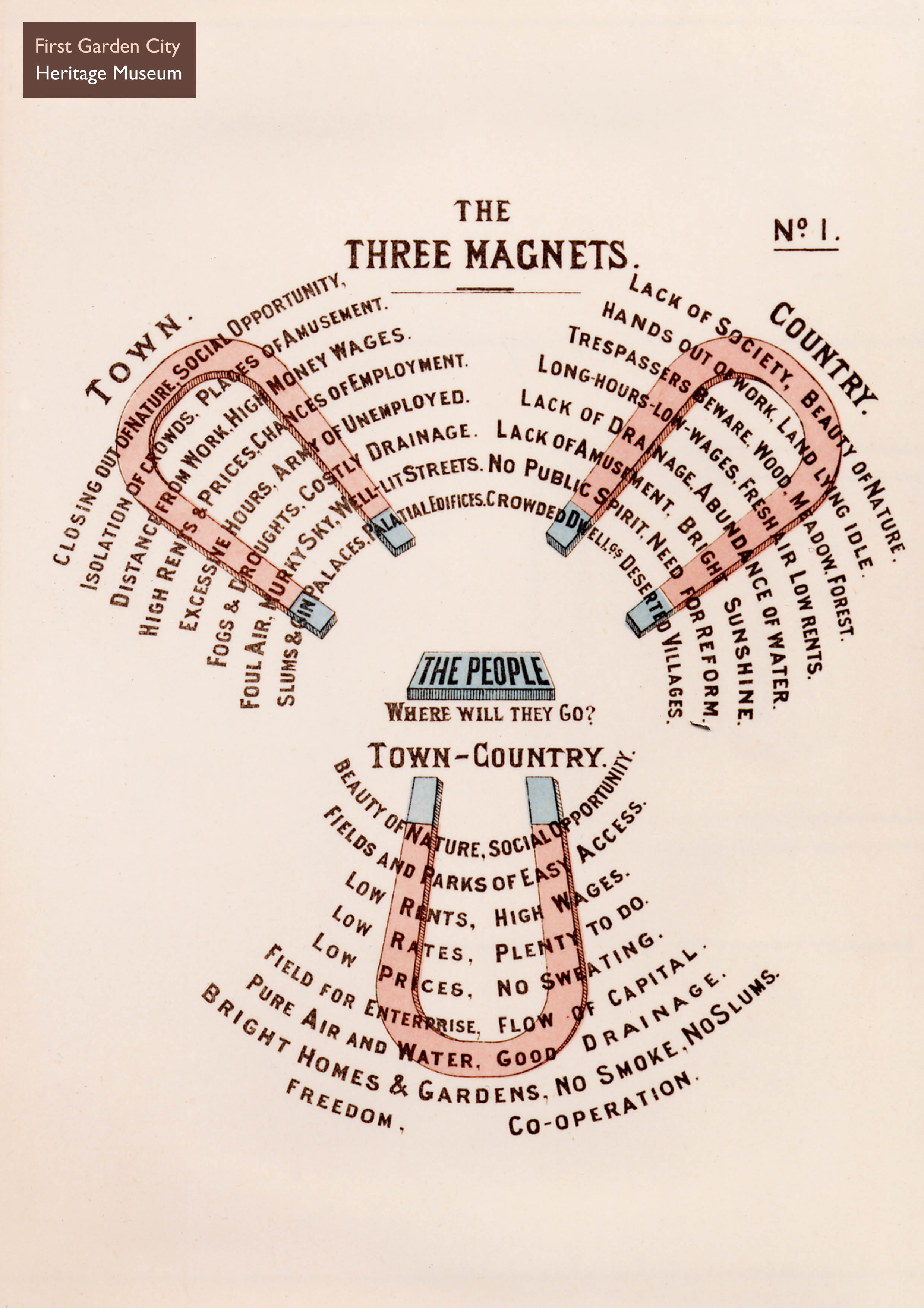

There is a clue here. If Liberals are able to see the world clearly, how the economic structures funnel wealth upwards, then we will sound like populists. But it is right that we should, but Liberal populists.

The difficulty is that it is hard to construct a new political language which is both tolerant and internationalist – but also furious at the way the world is currently arranged. That does not advertise our intention to tinker, but proclaims our determination to reform.

But that is what we have to do.

Clegg was quite right when he said that, as a nation, we are better when we are open-minded and work with other countries and peoples. That had resonance but it isn’t enough to win. Nor was the revelation that Farage wants to dig up the north of England for fracking.

And the next generation depends on us winning.